Edward Gibbon’s magisterial history of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire was published during the early years of the American Revolution.

The word revolution implies a turning of things, as a wheel turns on an axis. A wheel is meant to turn and keep turning. If it stops turning, it no longer performs the function of a wheel. Perhaps a revolution is a sudden increase in the speed of the turn, but the wheel keeps turning regardless.

Some will claim that a revolution has failed or that it suffered from some internal flaw if the reality that the revolution brought into being does not last forever. But the world is always changing and nothing lasts forever. The thunderbolt rules all things.

The metaphor of the turning wheel suggests some kind of historical cycle. Nature moves through predictable cycles, so it seems natural for men to imagine that their cultural and political worlds would also move through predictable cycles.

Many have tried to decode and explain the cycles of history, especially as our view of the human story expanded beyond our sight and living memory.

Since Gibbon’s enlightened age, the libraries of men have accumulated many more books and many more histories. A history is just a story and sometimes a just-so story. That’s important to remember when the Last Men are blinking at you with their innocent—but absolutely insistent—certainty.

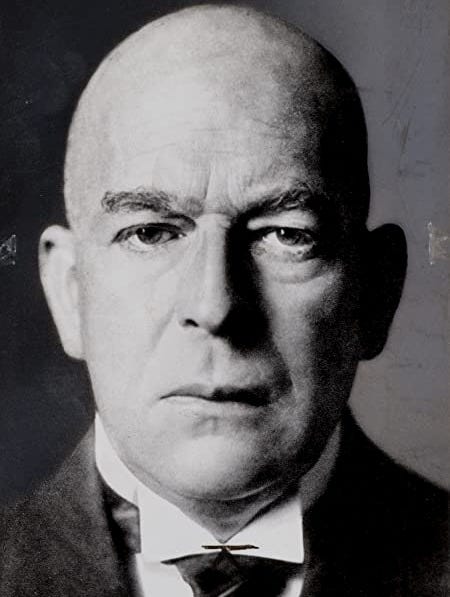

In the early 20th Century, a German named Oswald Spengler penned an impressive doom-tome titled The Decline of the West. The northern Europeans do love their cloudy prophecies of impending ruin.

The terminal prognosis of the Scandinavians was delivered by a witch, but if you had

to imagine the expression of a man who would foretell the fall of the West in exhaustive detail, you could do no better than Spengler’s brooding scowl.

America rose to global prominence after Spengler died, and many good and bad things have happened since the 1930s.

Yet more theories about the cycles of history, empires, and generations were published in the latter half of the 20th Century. History was supposed to end a while back, either metaphorically—à la Fukuyama—or physically, by nuclear war, global warming, or any number of B-Movie disasters. I was recently reminded by a meme that it has been 25 years since the Y2K scare, during which quite a few people believed that all of the world’s computers would crash and send us back into the dark ages. But that never happened, and the wheel kept turning.

In the 2010s, in response to postmodernism, peak feminism, institutionalized discrimination against men—especially white or “Western” men—and the obvious and inescapable signs of social, cultural, and physical decay in the Western world, many revisited the subject of Western decline. Spengler was rediscovered in dissident circles, as was the work of esoteric Italian perennialist Julius Evola.

For a generation of young men who were profoundly unimpressed with and even marginalized by the “social progress” hailed by progressives—the idea that we were living in some “fallen age” gained popularity.

Thanks to 21st-century English translations of Evola’s works, it became fashionable to blame contemporary social problems on the Kali Yuga, or “Age of Kali” from Hindu scriptures. This idea became wildly popular in online circles despite the fact that, according to most Hindu sources, we’ve been in the Kali Yuga for over 5,000 years—which includes just about every good and bad time in Western history, including whenever it is that you believe it peaked.

In Fire in the Dark, I wrote about our somewhat unique perspective. We have access to more information about the history of mankind than any man who has ever lived.

That doesn’t necessarily make us “smarter” than our ancestors, and it doesn’t necessarily mean that we understand that information or even truly know what happened. As I mentioned earlier, sometimes histories are just stories or just-so stories, and we don’t know as much as we often think we know.

But, from what we can presume to know, we are able to observe patterns in history in ways that would have been unimaginable to our predecessors—most of whom could never know with half as much certainty what had happened a thousand years prior or what was happening just a few thousand miles away.

I’ve called this “The Hliðskjálf Dilemma,” referencing Odin’s “mountain shelf” or “seat” from which he could see all things.

To our benefit, we have all of this data we can use to—in theory—make better or at least different decisions than we might have made with less information.

However, this immediate access to information also creates a scenario in which it is too easy to believe that everything is known and also possible to know or believe that one knows too much.

Vituð ér enn, eða hvat?

We have a vantage from which we can see far beyond human scale—more than our minds evolved to comprehend. Just as we cannot truly imagine, much less care about a million people—what can a thousand years mean to a monkey unlikely to reach one hundred years of age?

Many have the sense that they must place their thoughts within the history of human thoughts or check to make sure no one else has written the same words in the past 5000 years. Information about the past can certainly enrich our thoughts, but this five-thousand-year stare can also be paralyzing.

Say what you have to say as a man living right now, as alive as any man has ever been.

“…just people, living in the moment.”

Likewise, it is tempting to map out the cycles of history and try to place ourselves within those cycles.

But we cannot truly see the forest while we still live so close the trees. And the living always live close the trees.

We will always see our own time differently than it will be seen by those in the future, observing from a seat yet higher.

The decline of the West is just another story.

The idea of the West as a cohesive body that can live or die is also just a story. It’s a story about a variety of distinct cultures, peoples, ideas, and languages that have changed a great deal over a very long period of time. Tribes, kingdoms, republics, and empires who hated each other enough to fight countless bloody wars--all of these people tied together for history with a bow, singing kumbaya through the millennia.

Perhaps that is very useful for certain purposes.

But what is the utility of believing oneself to be living in a doomed or fallen age?

How does this make life better or more fulfilling?

How does it make one more prosperous?

Change is a constant, turmoil is a constant. Have men not always had complaints?

Of course they have.

But, if we want to live in a Golden Age—if we truly want to live in one and not just complain that we missed it—don’t we first have to believe that it is possible?

And if we believe it is possible that we could live in a Golden Age, don’t we also have to want to live in a Golden Age?

And, if we want to live in a Golden Age, don’t we have to be willing to work to create one?

The last few decades have been characterized by so much yearning for disaster and collapse—so much waiting for the end. So many men want this nihilistic fantasy. If we truly want to live in a Golden Age, we must recognize them as our enemies—as agents of death and the Dragon. For it is one thing to want change and another to just—as the man said—want to “watch the world burn.”

If you just want to watch the world burn, then fuck you.

If you always make the perfect the enemy of the good because you consciously or unconsciously believe that worse is better—because you are broken and constitutionally unable to tolerate happiness—then fuck you.

There is a sense of opportunity in the air.

For decades, progressives and the left possessed all the visionary energy and momentum.

You could hear their dreams and their enthusiasm in the music of the age. You could feel it. It was infectious.

[Someone, play “Can You Feel It” by Jackson Five]

But they had their chance.

Their dream sounded good, but it was rooted in the denial of human nature and the Gods of the Copybook Headings returned with terror and slaughter.

They had their chance, and they only succeeded in making the world uglier, dirtier, sicker, more hateful, more dangerous, and less free.

People believed in the dream and pretended they didn’t see it for years.

But they see it now. And they stopped believing.

Can you feel it?

There is room in the world for a new dream.

A dream of strength, beauty, health, and prosperity.

A New Golden Age.

No one man is going to deliver us a Golden Age on a silver platter.

We have to WANT a better future and WILL IT INTO EXISTENCE.

Don’t you WANT to live in a Golden Age?

Man, if you don’t want to live in a Golden Age, then fuck you.

We are monkeys who live for a hundred years.

Know this:

Whatever has happened is just a story and whatever will happen is just a dream.

No matter what happens, THIS is OUR time.

And it’s the only one we’ll get.

NOW is our Golden Age.

Can you feel it?

Stay Solar ऋत